The murder of Jamal Khashoggi - investigated with Google Trends

Jamal Khashoggi was a Saudi journalist and prominent government critic who wrote for the Washington Post, among other publications. He campaigned for freedom of the press and criticised Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in particular. On 2 October 2018, Khashoggi was murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul – an internationally high-profile case that put Saudi Arabia under considerable diplomatic pressure.

In this context, we want to analyse the search behaviour at that time, in particular conspicuous search queries that provided early clues about the perpetrators. At the time of data collection, there were initial suspicions, but neither evidence nor confessions. As the case has now been at least partially solved, we can review the data collected at that time to determine its validity and reliability.

It should be noted at this point that we are using the higher-resolution live data, but also the less precise historical data from Google Trends. We want to examine how this data can be transferred to verified incidents. The live data can no longer be reconstructed at this point in time due to the fact that it was collected a long time ago.

Time of disappearance

Jamal Khashoggi disappeared from the Saudi consulate building in Istanbul on 2 October 2018. Turkish media reported that a 15-member special team had already arrived from Saudi Arabia the day before. We are now investigating whether there are any indications in the available data that the offence may have been planned.

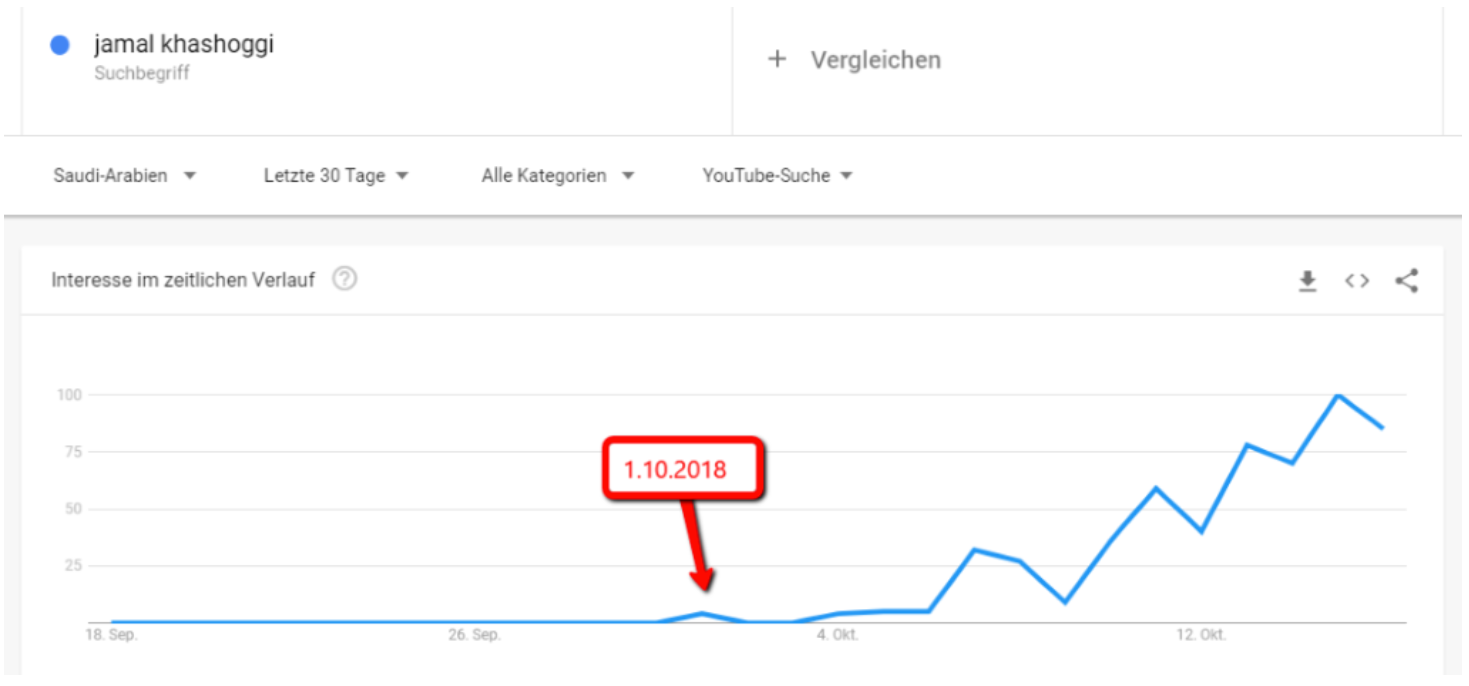

To do this, we first analyse the search volume for his person in Saudi Arabia. It is striking that there were indeed more searches for ‘Jamal Khashoggi’ before 2 October 2018.

Search via YouTube

It is also notable that searches were conducted not only through general Google Search but specifically on YouTube for video material related to Khashoggi — possibly to make it easier to identify him later.

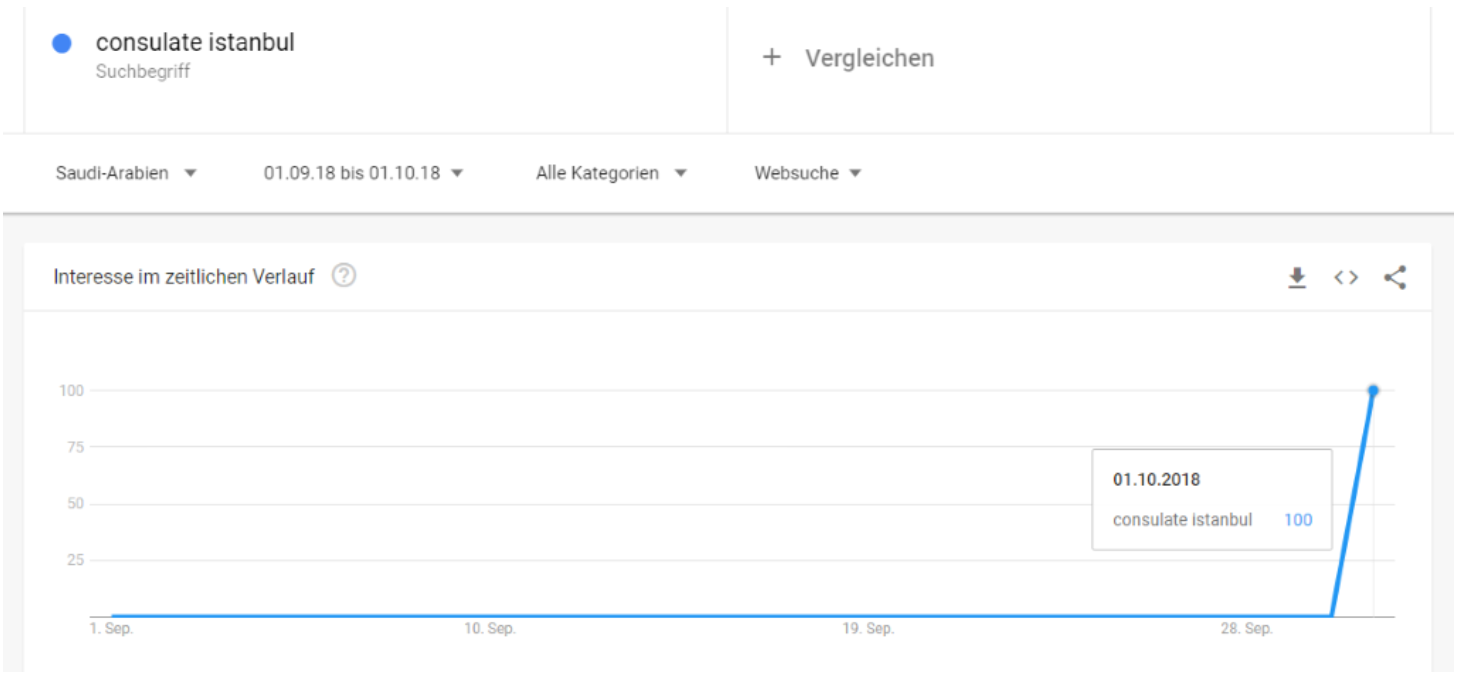

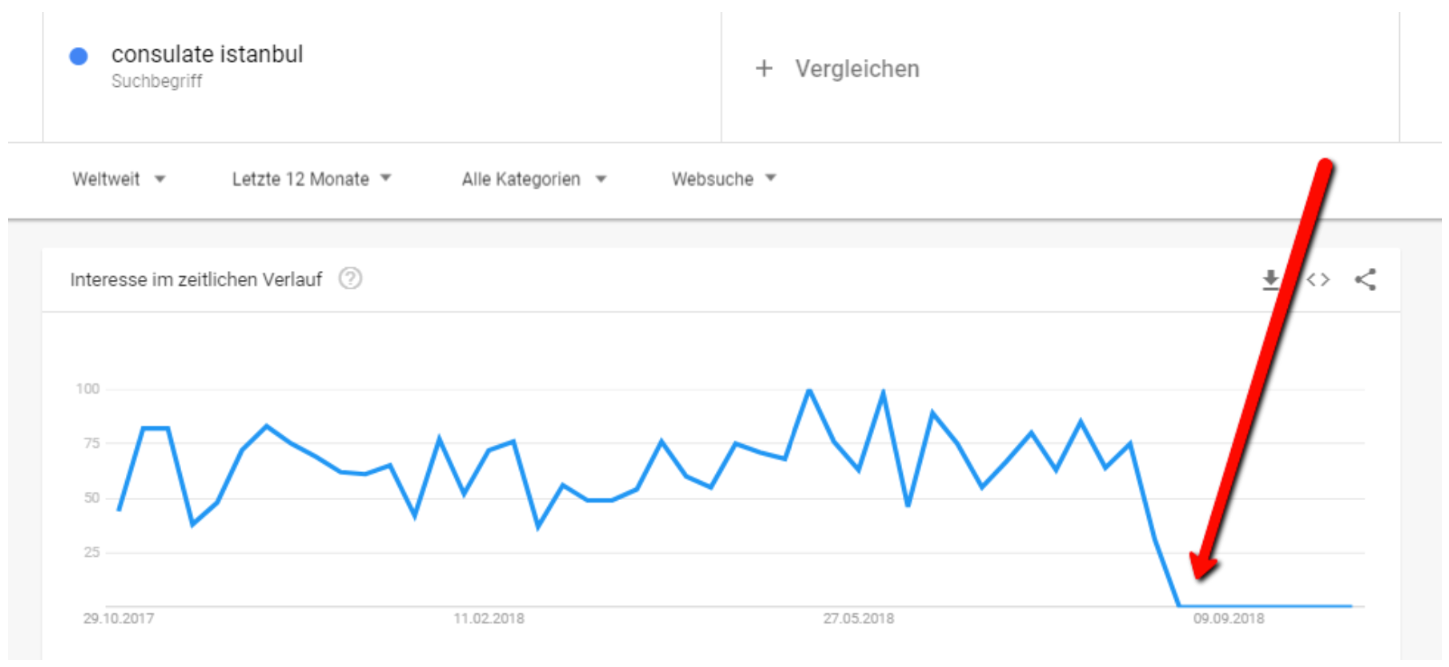

Crime Scene: The Consulate

On October 1 — just one day prior to the assassination — a significant uptick in search activity related to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul was recorded, originating from within Saudi territory.

These queries may have been associated with the logistical planning of a trip or visit. However, it is equally plausible that they were intended to monitor media coverage or assess public information related to the consulate — possibly as part of a situational awareness effort in anticipation of the forthcoming operation.

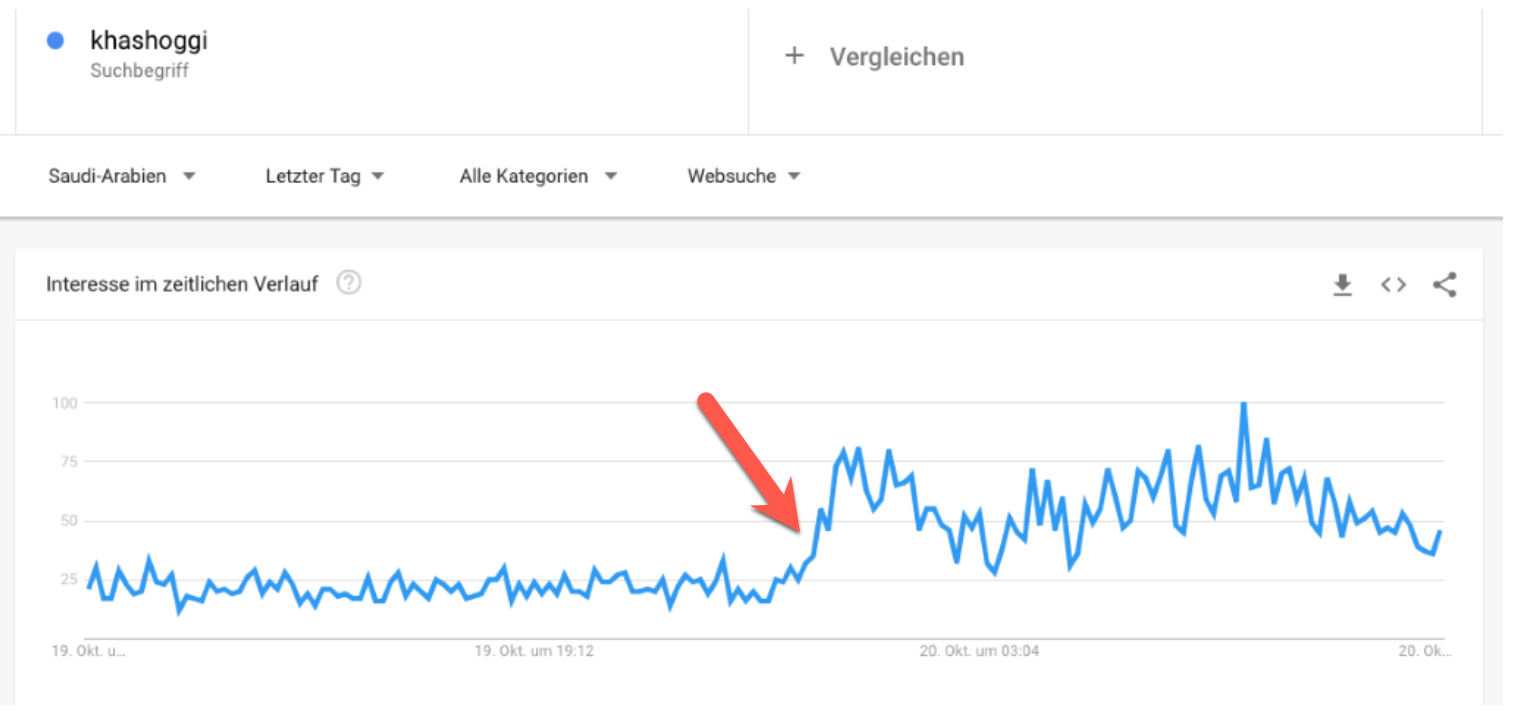

Press Statement on the Night of October 20, 2018

Until that point, the Saudi royal family had categorically denied any involvement in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi. However, in the early hours of October 20, 2018, the state-run Saudi Press Agency (SPA) issued the first official admission of partial responsibility.

The statement did not describe the act as premeditated, but rather framed it as an accident — claiming that Khashoggi had died during a “fistfight.”

The unusual timing of the release — during the night — suggests an attempt to minimize public attention and media coverage.

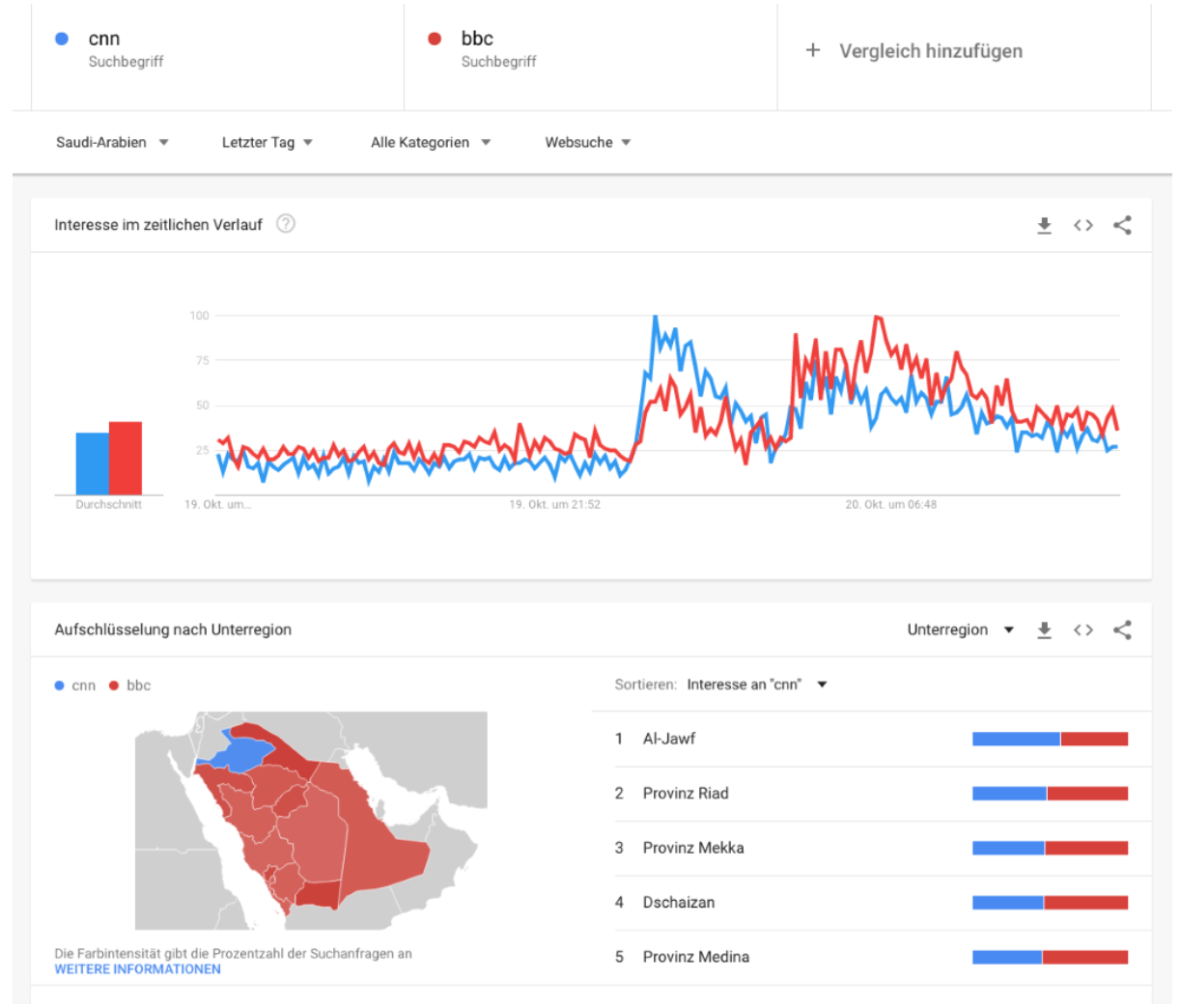

Monitoring of Foreign Press

The increased interest of Saudi users in international news coverage is also reflected in the following data. In the early morning hours of October 20, there was a noticeable spike in search queries for “BBC” and “CNN.”

This suggests a targeted effort to access current reports from international media outlets — possibly to assess the global reaction to the official Saudi press statement, or to compare external reporting with the kingdom’s own narrative.

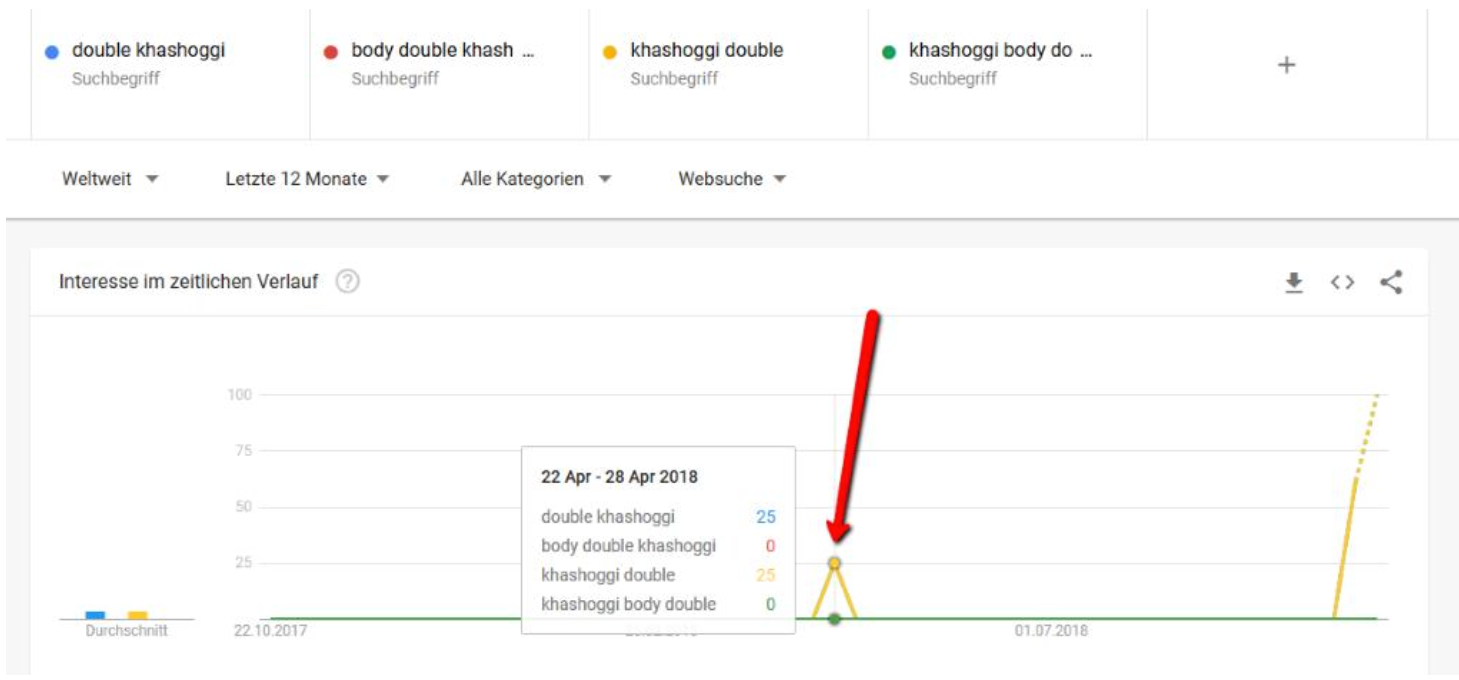

Indications of a Body Double

On October 23, 2018, Turkish investigators announced that they had found evidence suggesting the use of a body double for Jamal Khashoggi. To support this claim, they released corresponding video footage.

It appears that the double was intended to exit the consulate — presumably to be seen by bystanders — in order to create the impression that Khashoggi had left the building alive, thereby concealing the murder and, in particular, the dismemberment of his body.

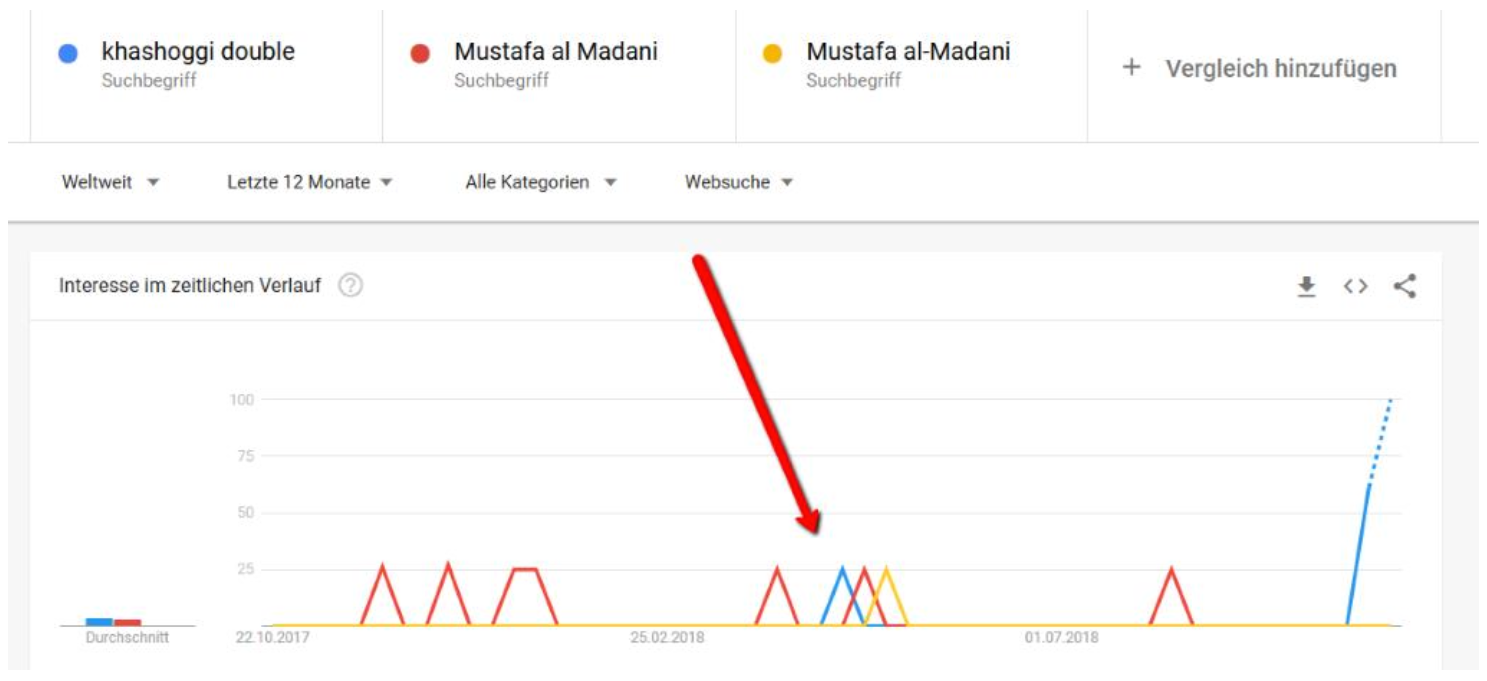

Notably, as early as April 2018, search queries were recorded that may indicate a targeted attempt to identify or recruit a lookalike. However, it should be noted that the available data in this regard is not particularly strong.

Turkish investigators later identified the body double as Mustafa al-Madani. Notably, this name had also been searched on Google in the months leading up to the incident.

Data Cut-Off Following Press Conference

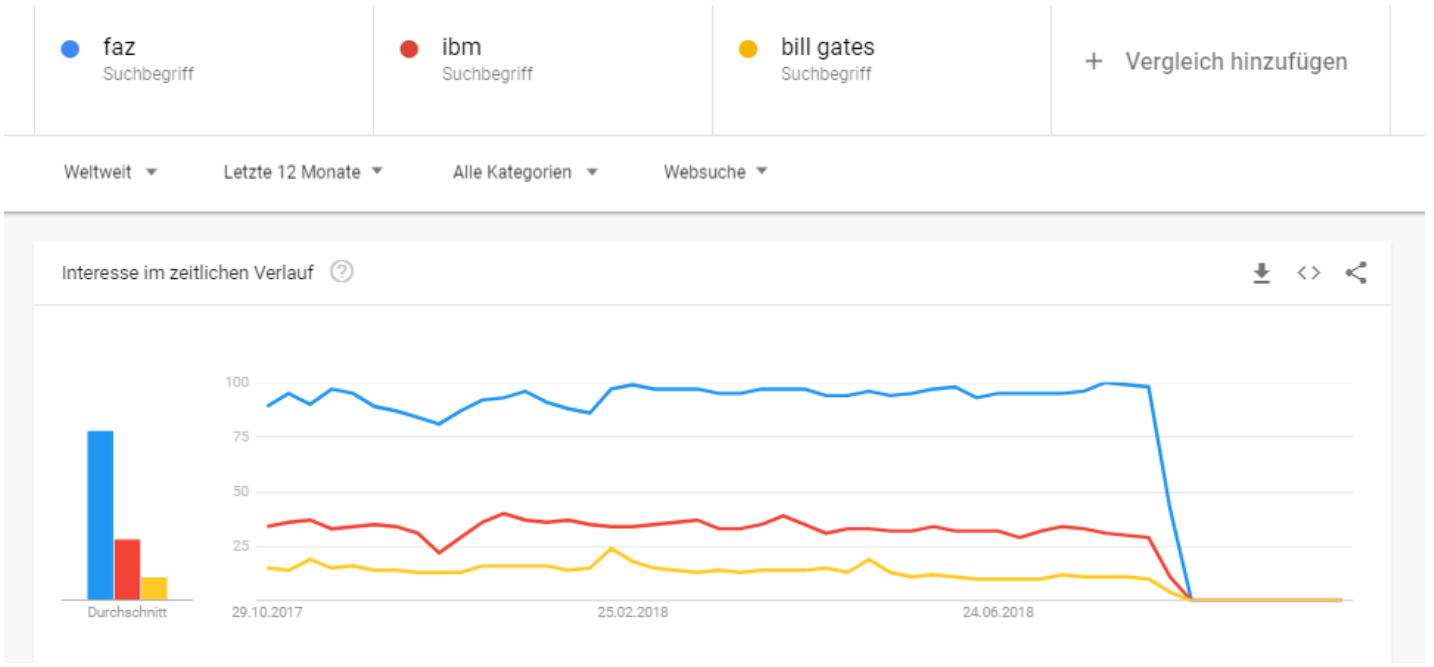

On October 23, 2018, the Turkish president presented key findings in the Khashoggi case during an international press conference. Immediately afterward, Google Trends shows an abrupt data cut-off — with no search data available for the period following August 21, 2018.

The following graphic clearly illustrates this disruption. While a direct causal link between the release of sensitive information and the disappearance of data cannot be definitively proven, the timing raises legitimate questions about transparency and possible external interference.

It was not only Khashoggi-related search queries that disappeared — no data was shown for any search term worldwide. Six hours later, Google resumed displaying complete datasets.

Attempt to Erase Digital Traces

Starting on October 15 — five days before the official admission — a noticeable spike appeared in search queries such as “history.google.com,” “history.google.com delete,” and “history.google.com delete all.”

This pattern suggests a deliberate attempt to erase digital traces from Google’s records. The clustering of such search terms indicates an awareness of digital traceability and an effort to conceal potentially incriminating activity after the fact.

Does this imply that the incident was not accidental after all?

Conclusion

For this investigation, both real-time and historical Google Trends data were analyzed. The findings reveal that suspicious search patterns in Saudi Arabia were already detectable prior to October 2, 2018 — the day Jamal Khashoggi was murdered. These included increased queries related to Khashoggi himself, the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, and later, search terms associated with deleting Google search history.

There are also indications — supported by earlier search queries — pointing toward the possible use of a body double. These patterns align in a remarkably consistent manner with the sequence of events later confirmed by official sources.

In retrospect, it can be stated that the data collected suggested a planned and targeted operation even before the Saudi government officially acknowledged any intent. The structure and timing of the search activity appeared coordinated enough to raise early suspicion of deliberate preparation.

It is important to emphasize: the search terms themselves were not inherently suspicious — terms like “Jamal Khashoggi” or “Consulate Istanbul” can be legitimate within a political context. What stood out was the targeted and moderate increase in these queries immediately before the incident. This discreet clustering within a narrow timeframe suggests operational activity — likely intended to avoid attention while still gathering the necessary information in advance.

Another notable observation: no clear attempt was made to conceal the geographic origin of the search activity. All suspicious queries were traceable to Saudi Arabia. This may indicate either a lack of awareness regarding digital visibility or the assumption that such queries would not, in themselves, raise suspicion.

Finally, the complete data cut-off in Google Trends shortly after the Turkish president’s press conference on October 23, 2018, stands out — affecting not only Khashoggi-related searches, but all global search terms. Whether this was a technical issue or an intentional data restriction remains unclear — but the timing is striking.

Critical Assessment of the Data

In principle, all data provided by Google Trends should be approached with a healthy degree of skepticism — especially when dealing with very low search volumes.

For example: Could it be that the increase in searches for “consulate istanbul” from Saudi Arabia actually occurred on the day of the incident, rather than the day before? Are the data inaccurate, or might there be an entirely different reason for the observed spike in search interest?

It is essential to always evaluate such data in a broader context and assess their temporal consistency. Individual search activities should never be interpreted in isolation.

At the end of such analyses, we do not arrive at classical forms of evidence, but rather at recommendations — indications that warrant further investigation.

Overall, the investigation demonstrates that Google Trends data — when used in combination with both real-time and historical datasets — can be a valuable tool for identifying early digital warning signals.

While they do not replace a formal forensic chain of evidence, such data can play a crucial role in pattern recognition and hypothesis formation — especially in cases where efforts are made to obscure events or control the flow of information.